In 1717 England, half the population had barely enough food and shelter to survive. Local churches gave relief only to the pitifully poor who were elderly or disabled. Work was scarce. The few who received public assistance were forced to wear a blue or red “P” on their clothes to designate their status – “pauper.” But across this bleak landscape, the Enlightenment was dawning, along with new ideas about philanthropy. A new fraternity was dawning with it. Freemasonry held relief up alongside truth and brotherly love. All brothers, it said – and indeed, all mankind – were bound by a “chain of sincere affection.”

18TH CENTURY

The Grand Lodge of England wasted no time setting up a safety net for brethren. By 1725 it had established a central Fund of Charity for Masons and their families, and began organizing a committee to oversee it. (According to Masonic scholar John M. Hamill in his 1993 Prestonian lecture: “Like many good Masonic committees it met regularly, argued long, presented an unworkable scheme, and was sent back to think again.” The committee was officially formed in 1727.) It was authorized to give five guineas for each relief case it heard, and presented special cases to the grand lodge. Lodges could contribute to the fund, and the position of grand treasurer was created to manage it.

From the beginning, “the Craft gave quietly but generously to many non-Masonic charities…” noted Hamill. In one example from 1733, English lodges took up a collection to help settlers in the American colony of Georgia. In the 1770s and 1780s, at the urging of Emperor Alexander I, Freemason Nicholas Novikov introduced modern programs such as charitable schools and famine relief, and created the Friendly Learned Society, an educational-charitable society that provided aid to those who could demonstrate need. Other prominent Russian Masons later organized the charitable endeavors, committees, and institutions that eventually led to the founding of the Imperial Philanthropic Society in 1816 – the country’s first officially sanctioned charitable society.

19TH CENTURY

In 1788 in East London, the Premier Grand Lodge opened what would become the Royal Masonic Institute for Girls – a school for daughters of “indigent or deceased Free Masons.” Around the same time, the rival Antients Grand Lodge began providing grants for clothing, food, and education for the fraternity’s needy boys, and after the two grand lodges merged, a residential school for boys was opened. These proved to be precursors for Masonic orphanages and homes for widows and elders.

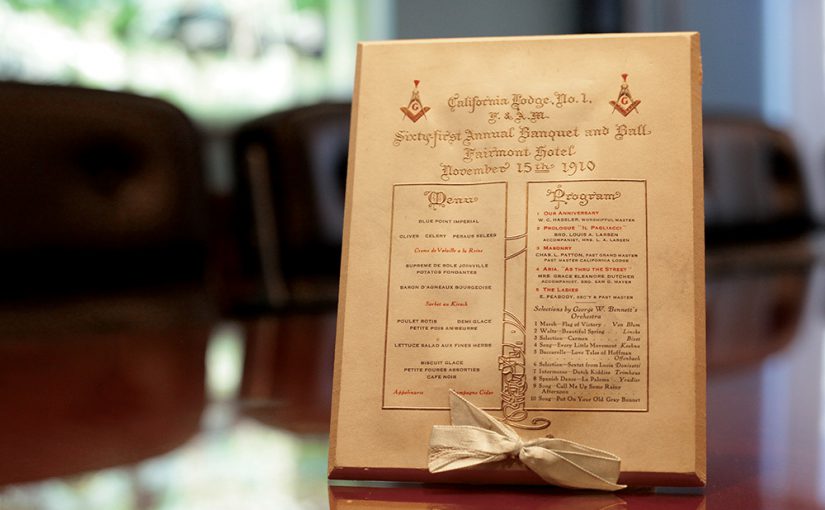

Wherever the fraternity spread, it answered the call of relief. In California, as many settlers’ dreams of gold gave way to poverty and disease, lodges provided food and nursed the sick. During the cholera outbreak of 1850, 300 Masons raised $32,000 and opened a hospital at Sutter’s Fort.

To reduce the pressure on individual lodges, many grand lodges, including the Grand Lodge of California, eventually created regional boards to organize and disseminate relief funds to fraternal family in distress. In 1886, 19 delegates from Canada and the United States met in St. Louis to form the General Masonic Relief Association of the United States and Canada. The new association helped coordinate relief activities of lodges and relief boards throughout the continent, from helping elderly brothers transition into nursing homes to helping grand lodges distribute charitable funds. It also worked to deter fraudulent claims for relief, sending out bulletins with headlines such as “beware of this moocher” and featuring the description and aliases of Masonic impostors at large.

Across the Atlantic, the United Grand Lodge of England had by this time established a fund to provide annuities to elderly brethren, wives, and widows in need, and even opened a brick-and-mortar residence. Many American grand lodges were supporting Masonic colleges and seminaries by then – in 1847, Pennsylvania, New York, Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Florida, and Tennessee boasted Masonic schools – but it wasn’t until 1867 that the first U.S. Masonic home for widows and orphans opened, established by the Grand Lodge of Kentucky. Other grand lodges followed, and within a few decades, dozens of Masonic homes had opened in the U.S. In 1898 the Grand Lodge of California opened its Masonic Widows and Orphans Home in Decoto (now Union City), thanks to donations by approximately 16,000 California Masons. A decade later, it established a second community, exclusively for Masonic orphans, in the San Gabriel Valley of Southern California – today’s Covina Masonic Home.

WORLD WAR I AND AFTER

During World War I, many grand lodges and lodges gave generously to support their nation’s armed forces, including military hospitals. A group of English brothers from Malmesbury Lodge No. 3156 went even further, opening the Freemasons’ War Hospital and Nursing Home in West London in 1917. (Later known as the Royal Masonic Hospital, it earned a sterling reputation and remained open long after the war.)

By 1919, prompted by the War Department’s request to work with just one coordinated Masonic charity, 49 U.S. grand lodges formed the Masonic Service Association to send relief funds for their servicemen. After the war, the organization continued collecting and distributing funds for national Masonic efforts such as disaster relief. By 1938, it had raised and disbursed nearly $1 million for natural disasters in Japan, Florida, Mississippi, Puerto Rico, Kentucky, and Austria.

It wasn’t the only Masonic organization answering new calls for relief. In 1922, a tristate committee of Arizona, Texas, and New Mexico grand lodges planned a sanatorium for Masons and dependents struck by tuberculosis. In Portland, Oregon in 1920, the Imperial Session of the Shriners unanimously passed a resolution to establish its now renowned hospital for children. That same year in California, faced with a devastating teacher shortage, the Grand Lodge proclaimed the first Masonic Public Schools Week – a precedent that would evolve into a legacy.

Examples of innovative, compassionate relief appear in the early records of lodges and grand lodges worldwide. In California’s Annual Communication report from 1906, Harry J. Lask, secretary of the San Francisco Board of Relief, wrote of the fraternity’s response to the earthquake that had ripped through San Francisco that spring. “One touch of nature made the whole world kin,” Lask wrote. “As disastrous and sorrowful was the calamity, it had its good effect of making all as one family, and binding the tie of brotherly love and fraternity stronger.”

“GIVE, GIVE, I PRAY YOU!

“GIVE, GIVE, I PRAY YOU!

Thomas Starr King – preacher, abolitionist, scholar, Freemason – was known as “the orator who saved the nation” for his role in persuading California to side with the North in the Civil War. He was also responsible for a massive war relief program.

Starr King led the Pacific branch of the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC), the forerunner of the American Red Cross. The commission distributed food, clothing, and medicine to sick and wounded Union soldiers, relying on contributions from the American public. By 1862, after a series of Union defeats, it was nearly bankrupt. Then Starr King began fundraising in the Golden State, traveling at his own expense from cities to mining towns to farming counties. At a San Francisco rally, he pled: “Give, give, I pray you… Shall it be said that rich and generous California was the only state whose blood did not bound in unison and sympathy with her loyal sisters? Shall history say that electric California was alone laggard?”

In the end, California contributed $1.25 million to the USSC – more money than any other state. Starr King was chiefly responsible.

Upon his death in 1864, at the age of just 39, the Boston Evening Transcript wrote that Starr King had “toiled like an angel of mercy” for those called to the battlefield. “His words of earnest entreaty coined hundreds of thousands of golden dollars for the treasury of beneficence. Thus striving, he has died as much a hero as he would had he fallen leading an army to victory.”

Photo Credit: The Library and Museum of Freemasonry, London (Charity Engraving) and Masonic Service Association of North America(First Meeting Photography)

Permission to reprint original articles in CALIFORNIA FREEMASON is granted to all recognized Masonic publications with credit to the author, photographer, and this publication. Contact the editor at editor@freemason.org.