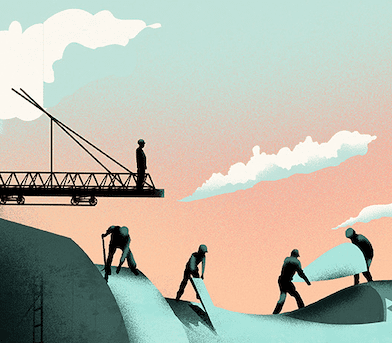

In any building’s foundation, minor cracks can eventually lead to major problems. It starts any number of ways—a mistake during construction, a catastrophic event, the simple wear and tear of time. If you spot a crack early, you might be able to repair it yourself. Let it go too long and the damage will almost certainly get worse. After enough time, it can bring down the whole structure.

In any building’s foundation, minor cracks can eventually lead to major problems. It starts any number of ways—a mistake during construction, a catastrophic event, the simple wear and tear of time. If you spot a crack early, you might be able to repair it yourself. Let it go too long and the damage will almost certainly get worse. After enough time, it can bring down the whole structure.

That’s the case with Masonic lodges, too.

“You can usually sense the minute you walk into a lodge if there’s conflict,” says Gary Silverman, past master of Saddleback Laguna Lodge No. 672. “It’s almost palpable. There’s a fracture. You can see it in the dining room. There’s a group over here and a group over there, and never the twain shall meet.”

Silverman should know. As a crisis management consultant, he’s made a career out of conflict resolution. He intervenes with businesses experiencing explosive growth or about to go under, helping CEOs and other leaders work through their issues to build healthier teams.

He now takes the same lessons for struggling businesses and applies them to lodges. At Masonic leadership retreats, he often gathers lodge leaders in candid, confidential discussions about the problems keeping them up at night. Over the years, he’s visited many of their lodges to facilitate conflict resolution.

As a result, he’s been around more lodge discord than most. He’s seen conflicts that started as innocent misunderstandings harden into grudges. He’s seen conflicts caused by the pressure a lodge experiences during a time of growth or change. He’s seen conflicts about money and status and personality clashes. More than that, he’s seen them start with someone who simply wants to be heard. “Interpersonal conflicts usually come from a common issue: Somebody has a desire to contribute and they’re not being allowed to,” he says. “Often all the person wants is to be listened to and have their opinion valued.”

Whatever the circumstances, take it from Silverman: Conflicts don’t just flare up at troubled lodges or growing lodges, old lodges or new. They happen everywhere.

No matter what the cause of such problems is, learning to address them is one of the most important issues a lodge faces. In membership surveys, Masons consistently say that issues related to lodge harmony—interpersonal relationships, politicking, bickering—are the greatest contributor to their overall feelings toward the fraternity. Those who feel heard and respected remain active; those who don’t tend to drift away.

For many lodge leaders, navigating the tangle of intralodge beefs isn’t just challenging—it can feel totally outside their skill set. Yet a lodge master’s greatest responsibility isn’t just balancing the books or organizing events; it’s maintaining lodge harmony. Luckily, Silverman says, the tools they need are all available within the context of Masonic teaching.

When Silverman meets with members who are at odds, he usually begins with a question: Why did you join? If members can focus on that shared experience, they might find the motivation to stick around and talk. “Both parties must be invested in a resolution,” Silverman says. In other words, they have to care enough about the relationship to begin the hard work of fixing it. For that to happen, they often need to recognize that they share a common goal. “That gets the focus where it needs to be.”

Once they agree to that, it’s a matter of following the lessons every candidate learns in the first degree: Meet each other on the level. Part on the square. Walk uprightly.

Of course, like most of Masonry’s lessons, this is easier said than done.

Stirred by her words, Goodman decided to run for student body president. He won with a call-and-response campaign speech inspired by Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, and The Autobiography of Malcolm X. And so for that final year of high school, the self-described introvert balanced his nascent political career with his true passion, music. The same year, Goodman joined a local ska-punk band making its name at backyard ragers around Long Beach. They called themselves Sublime. Within a few years, they’d be one of the biggest bands in the country.

Stirred by her words, Goodman decided to run for student body president. He won with a call-and-response campaign speech inspired by Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, and The Autobiography of Malcolm X. And so for that final year of high school, the self-described introvert balanced his nascent political career with his true passion, music. The same year, Goodman joined a local ska-punk band making its name at backyard ragers around Long Beach. They called themselves Sublime. Within a few years, they’d be one of the biggest bands in the country.

That rings true for others, as well. “I call Marshall when I’m going crazy,” says Chad Wanke, mayor pro tem of Placentia, a small community northeast of Disneyland. “Or I call when I need someone to give me a different perspective, or to just vent to.” On paper, Wanke and Goodman make an odd couple: Wanke is a Republican, Goodman a Democrat. They find themselves on different sides of the aisle all the

That rings true for others, as well. “I call Marshall when I’m going crazy,” says Chad Wanke, mayor pro tem of Placentia, a small community northeast of Disneyland. “Or I call when I need someone to give me a different perspective, or to just vent to.” On paper, Wanke and Goodman make an odd couple: Wanke is a Republican, Goodman a Democrat. They find themselves on different sides of the aisle all the

Still, it was a considerable change for Casper, who’d owned an electronics manufacturing firm for years before getting into piano repairs. But approaching retirement, he figured he needed a new pastime—and piano tuning spoke to him. As his wife is a children’s piano instructor, he already had a built-in clientele.

Still, it was a considerable change for Casper, who’d owned an electronics manufacturing firm for years before getting into piano repairs. But approaching retirement, he figured he needed a new pastime—and piano tuning spoke to him. As his wife is a children’s piano instructor, he already had a built-in clientele.

Still, you won’t hear Vazquez complain. Neither will the other members of the 122-person Masonic lodge, which has distinguished itself in part by just how far its members are willing to travel to sit together each week. After visiting the out-of-the-way temple one day with friends, Vazquez knew immediately that the trip was one worth repeating. “Right when I stepped foot inside the lodge, I knew it was something special,” Vazquez says.

Still, you won’t hear Vazquez complain. Neither will the other members of the 122-person Masonic lodge, which has distinguished itself in part by just how far its members are willing to travel to sit together each week. After visiting the out-of-the-way temple one day with friends, Vazquez knew immediately that the trip was one worth repeating. “Right when I stepped foot inside the lodge, I knew it was something special,” Vazquez says.

In any building’s foundation, minor cracks can eventually lead to major problems. It starts any number of ways—a mistake during construction, a catastrophic event, the simple wear and tear of time. If you spot a crack early, you might be able to repair it yourself. Let it go too long and the damage will almost certainly get worse. After enough time, it can bring down the whole structure.

In any building’s foundation, minor cracks can eventually lead to major problems. It starts any number of ways—a mistake during construction, a catastrophic event, the simple wear and tear of time. If you spot a crack early, you might be able to repair it yourself. Let it go too long and the damage will almost certainly get worse. After enough time, it can bring down the whole structure.

To mend a damaged relationship, a lodge needs the courage to sit down and talk about the problem. And for that to be successful, it might need some help from a skilled facilitator—or, at the very least, some practice with difficult conversations.

To mend a damaged relationship, a lodge needs the courage to sit down and talk about the problem. And for that to be successful, it might need some help from a skilled facilitator—or, at the very least, some practice with difficult conversations. Masonry talks a lot about how to build a lodge. It talks less about how to fix one. But the same tools for building are used to make repairs. Take the square and the plumb. They remind Masons to treat one another fairly and with respect. That’s the way out of almost any conflict. In times of turmoil, they’re more important than ever. “I’ve heard it said: ‘A lodge should be a place where armor is neither required nor rewarded,’” says Chris Smith, a district inspector and member of

Masonry talks a lot about how to build a lodge. It talks less about how to fix one. But the same tools for building are used to make repairs. Take the square and the plumb. They remind Masons to treat one another fairly and with respect. That’s the way out of almost any conflict. In times of turmoil, they’re more important than ever. “I’ve heard it said: ‘A lodge should be a place where armor is neither required nor rewarded,’” says Chris Smith, a district inspector and member of