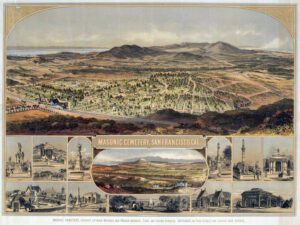

The final death knell came in 1930, when the city officially rezoned the area of Lone Mountain, which formally allowed the boards of the big four cemeteries to sell off their land and reinter their dead elsewhere. As the moves began, one cemetery at a time, caskets were dug up and transported south to the sleepy town of Lawndale, now known as Colma, the so-called “city of souls.” Today, Colma is home to 18 cemeteries. Nearly 1.5 million people are buried there, 1,000 times its living population.

With the cemetery’s closure imminent, the San Francisco Masonic Cemetery Association raised funds to purchase land for a new resting place in Colma called Woodlawn Memorial Park. (In 1996, Woodlawn was sold to a private corporation, but remains the largest de facto Masonic cemetery in the Bay Area.) Most of the bodies originally buried at the San Francisco site were dug up and transported to Woodlawn, though a few wound up at nearby cemeteries including Olivet Memorial Park, Cypress Lawn, and Greenlawn Memorial Park just a few blocks away.

Many, however, were never removed at all—an exceedingly common occurrence citywide during the great reinterrment period. One study found that at Golden Gate Cemetery (now the site of the Legion of Honor and the Lincoln Park Golf Course), only about 1,000 bodies’ remains were ever actually removed, leaving an estimated 18,000 still in the ground. (A museum excavation in 1993 uncovered 800 of them.)

At the four Lone Mountain cemeteries, the herculean task of digging up the deceased was, understandably, challenging. One report described it as “chaotic and hasty.” While many caskets could be moved intact, others were in various states of decomposition, and only some of the remains were moved. Others were left “wholly untouched,” according to a 2011 archaeological survey conducted on behalf of the University of San Francisco.

In the end, relatively few of the deceased were ever provided with new individual grave markers. Of the 20,000 people buried at the Masonic Cemetery, about 5,000 remains were claimed by family members and reinterred in Colma, according to a fraternity report at the time. The rest—up to 15,000—were, like the rest of the city’s unclaimed, placed in mass graves, their tombstones left behind. Even Masonic dignitaries met that fate: Among those moved to an unmarked grave in the common plot was Jonathan Stevenson, the first grand master of California. It wasn’t until 1954 that he was reinterred in the California № 1 lodge plot at Cypress Lawn and a memorial plaque was erected in his memory.

Last year, for the first time ever, the Masons of California launched a two-week social media campaign called #ImAMason designed to help raise awareness of the fraternity among our members’ online networks.

Last year, for the first time ever, the Masons of California launched a two-week social media campaign called #ImAMason designed to help raise awareness of the fraternity among our members’ online networks.

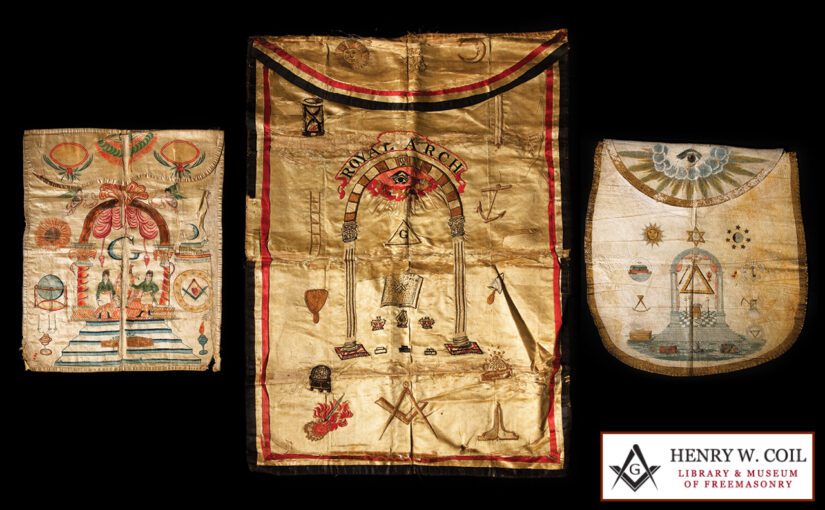

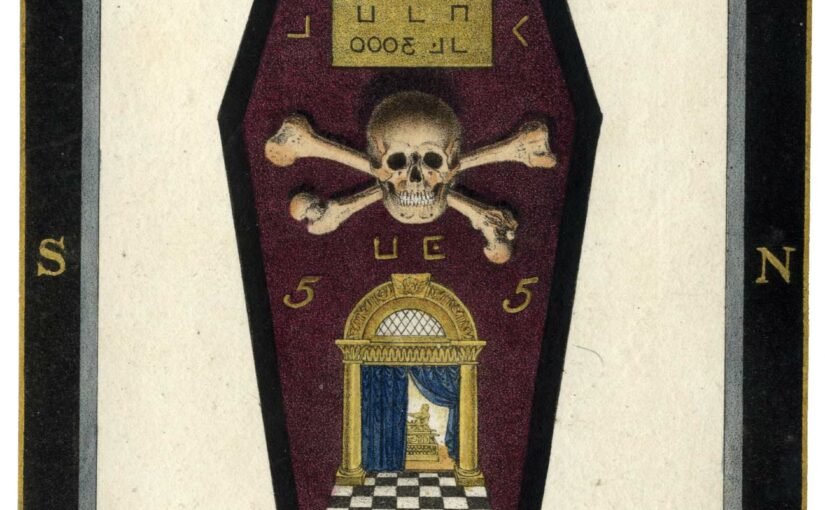

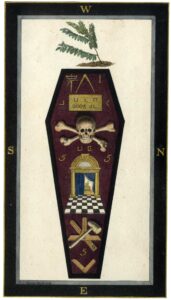

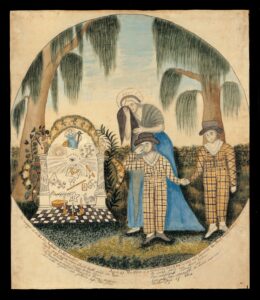

Today, these tend to be abstract ideas, jumping-off points for discussion of esoteric concepts. But historically,

Today, these tend to be abstract ideas, jumping-off points for discussion of esoteric concepts. But historically,  Any discussion of death and the afterlife inevitably leads to an ontological reckoning. To say that one believes in life after death or in the existence of the soul is an inherently spiritual statement, an expression of faith. Even distinguishing material and spirit, for some, raises uneasy metaphysical questions. It’s not surprising that for most Americans, death can be an uncomfortable topic.

Any discussion of death and the afterlife inevitably leads to an ontological reckoning. To say that one believes in life after death or in the existence of the soul is an inherently spiritual statement, an expression of faith. Even distinguishing material and spirit, for some, raises uneasy metaphysical questions. It’s not surprising that for most Americans, death can be an uncomfortable topic.