Originally published in the May/June issue of California Freemason. Read the digital magazine here!

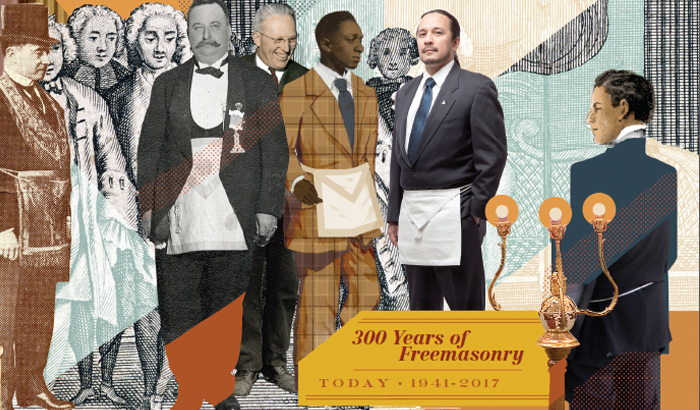

It takes a strong institution to abide for more than 300 years.

But it takes a remarkable one to endure through 300 years of social change and political upheaval on the scale Western civilization has seen. During the eras between the Enlightenment and the French and American revolutions, society experienced a transformation in how it was organized, how political institutions were formed, and, perhaps most importantly, how individual citizens interact with one another. Throughout this profound global change, not only did Freemasonry continue to exist; it served as a catalyst for positive change. How did Freemasonry evolve into the cornerstone of society today, and what factors have contributed to its endurance?

THE BROTHERHOOD BEGINS

The first Masonic lodges emerged in 17th-century Scotland when men who were not stonemasons by trade began to seek membership in stonemasons’ lodges. These “speculative Masons” emerged from a wide swath of society, but many were of the gentry. Although there are few definitive records, it appears that upper-class men – like Sir Robert Moray, a statesman and scientist – were attracted to lodges’ ritualized practices, intriguing secrecy, and friendships among members. In turn, these elite outsiders offered stonemasons a reliable source of dues and greater social prestige. Although speculative members joined at varying paces throughout the 1600s, the end result is clear: By the opening decade of the 18th century, at least 25 lodges comprising both stonemasons and non-stonemasons were established throughout Scotland.

Early Scottish lodges governed themselves autonomously and shared few standard operating procedures; each established its own rules of conduct and customs. This contrasted sharply with the Dutch, English, and French lodges that appeared at later dates, all of which followed regulations emanating from The Hague, London, and Paris respectively. The first efforts to standardize Masonic practices under a central authority began in 1716, when a group of London Masons agreed to hold an annual meeting and banquet on the feast day of Saint John the Baptist in order to encourage socialization between lodges. On June 24, 1717, masters of these same lodges constituted the first grand lodge.∗ During the first half of the 1720s, 24 lodges affiliated with the Grand Lodge in the capital, and additional lodges arose throughout continental Europe. Over the following two decades, the Grand Lodge of England continued to assume regulatory powers, transmitting basic guidelines for lodges and candidate admission over lodges throughout the entire kingdom, continental Europe, and colonial America.

A SPREADING FRATERNITY

As Voltaire’s “Letters Concerning the English Nation” (1733) and Montesquieu’s “Spirit of the Laws” (1748) testify, British politics and culture fascinated continental Europeans during the first half of the 18th century. There was a deep interest in Britain’s freedoms of religion, opinion, and association – with Freemasonry embodying the latter. In the 1720s and 1730s, lodges popped up in all corners of continental Europe, from Sweden to Italy. Bustling cities like Madrid, Paris, and Rotterdam, Holland were major Masonic hubs, but Freemasonry also spread to smaller locales with an established military presence or commercial ties to the Atlantic or Mediterranean worlds, such as the French regions of Le Havre and Valenciennes.

Like European Freemasonry, many American lodges were formed by British ambassadors, military personnel, and merchants. In 1730, the Grand Lodge of England appointed Colonel Daniel Coxe to charter lodges in the British colonies of New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania (though he apparently never exercised his authority). A few years later, Bostonian merchant Henry Price was appointed the “provincial grand master of New England and dominions and territories thereunto belonging,” responsible for cultivating Freemasonry’s North American growth.

After working under the aegis of Boston during the 1730s and 1740s, Philadelphia received a deputation from London. The Grand Lodge also allowed some American lodges to function independently from provincial authority, such as one in Savannah, Georgia, which began meeting in 1733. By the late 18th century, Freemasonry had grown along North America’s eastern seaboard and throughout the Caribbean, from Nova Scotia, Canada to the West Indies. Over the next century and a half, the craft spread westward. In 1848, the first lodge was formed in California; the state’s grand lodge was established in 1850.

EARLY DIVERSITY

Unlike the first speculative lodges, American and European lodges after 1750 welcomed diverse social tiers to their ranks. Founded in 1772, Saint Luke Lodge in Dijon, France, included skilled artisans, like plasterers and silversmiths. In the United States, clockmaker Emanuel Rouse of Philadelphia and printer Thomas Fleet of Boston were active Freemasons. Freemasonry appealed to many different types of men because it was a hybrid – amorphous sociability blended with diverse content. Fashionable cultural currents of the time, like mesmerism, occultism, and the pseudo-scientific teachings of colorful figures like Count Cagliostro (who claimed to possess psychic powers and created an esoteric ritual system of 90 dizzying degrees) found their place within Enlightenment-period lodges. In continental Europe, the variety of ritual styles contributed to Masonry’s allure. It was not considered to be a secret society – Freemasonry depended upon publicity to attract new members and to defend itself from accusations ranging from sodomy to atheism – but one that could impart hidden knowledge of the supernatural.

One colorful member was Robert Samber (1682-1745) of Hanoverian England. After briefly considering a clergy position, he began translating French works to English, including Charles Perrault’s children’s favorite, “Tales of Mother Goose,” but also pornographic tracts, such as the ribald “Venus in the Cloister,” the publisher of which was later condemned for obscenity. Samber’s Masonic connections were printed for all to see. A 1722 translation was dedicated to the earl of Burlington, likely a member of a York lodge in northern England. Samber was closely associated with two English Masonic leaders: the duke of Montagu, grand master in 1721, and the duke of Wharton, grand master in 1723. During this period, Samber also translated from French a treatise entitled, “Long Livers.” Keeping a Masonic audience in mind, he dedicated the alchemical text – which promised to reveal “the rare secret of rejuvenescency” – to the “Fraternity of Free Masons of Great-Britain and Ireland.” Within its opening pages, “Long Livers” praised Masonry as a “royal priesthood”; a universal religion, free of pagan idolatry but nonetheless maintaining “pompous sacrifices, rites and ceremonies, magnificent sacerdotal and levitical vestments, and a vast number of mystical hieroglyphics.”

This emphasis on religious tolerance within the controlled setting of the lodge reflected the inclusive universalism that preoccupied European and American Freemasons in the Enlightenment. Brethren were building upon a tradition of ecumenism that traced back to the mid-17th century. They particularly admired theologians Henry More and Ralph Cudworth, who emphasized religious tolerance among Christians. One of the founding fathers of French Freemasonry, Andrew-Michael Ramsay, placed Freemasonry squarely in the history of Christian brotherhood, for like “our ancestors, the crusaders,” he hoped Masonry would unify Christians into a “spiritual nation” that would transcend national, linguistic, and denominational differences.

ERASING RELIGIOUS DIVIDES

A notable difference between Anglo-American Masons and their continental counterparts was that the circle of tolerance was wider among the former than the latter. An anonymous orator from Boston spoke of his lodge in 1734 as “a paradise,” promoting a “universal understanding” among men of “all religions, sects, persuasions, and denominations…” This sharply contrasts a Berlin speech of the same period, which restricted Masonic membership to “all those who believe in Jesus Christ…” Non-Christians, even those who were initiated elsewhere, routinely found the doors of the fraternity closed to them in Germany, France, Spain, and Italy.

In 1746, the “English” lodge in Bordeaux, France, debated: “Can one initiate Jews into the order?” Bordeaux was a port city with an important Iberian Jewish population who were interested in Freemasonry. But the lodge secretary recorded that the proposition was “completely rejected.” Throughout the century, there was little evolution on this question. In 1783, a master in Le Mans stipulated that brethren must profess “ordinary religion.” But he went on to explain that this meant “to be good, sincere, modest, and a man of honor AND be baptized in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.” (The clarifying “and” was capitalized for emphasis.) This policy resulted in Jews’ and Muslims’ continued exclusion from many 18th century continental lodges.

Despite discrimination against non-Christians in some regions, however, Freemasonry overall clearly resonated with the Enlightenment ideals of religious tolerance among Christians of all stripes, which was first espoused by Pierre Bayle, a French Protestant living in exile in the Netherlands, and especially by John Locke in his landmark “Letter Concerning Toleration” (1689). Locke’s call for religious freedom was partly the inspiration for the American first amendment drafted 100 years later.

CORNERSTONE OF CIVIC SOCIETY

Notable Freemasons like George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, the Marquis de Lafayette, and others famously participated in both the French and American Revolutions; however, Masonry’s connection to these conflicts is complex. It is true that in officer elections and selective mixing of wealthy commoners and aristocrats, lodges were a quasi-democratic arena. But this did not contradict the ruling status quo of early modern Europe, since most Enlightenment-era Freemasons were remarkably deferential to existing political regimes and both absolutist and constitutional forms of monarchy.

Perhaps the most tangible connection between Enlightenment Freemasonry and revolutionary politics was Freemasonry’s emphasis on fostering civic virtue among brethren. When Washington wore his Masonic apron at the U.S. Capitol inauguration in 1793, he was sending an unambiguous public message that Freemasonry constituted the cornerstone of the new republic. He stressed that it taught “the duties of men and citizens” and represented a “lodge for the virtues.”

During the tumultuous times of the late 1700s, American Freemasonry sought to be a beacon of stability. Members hoped that Masonic values and strong friendships could heal fractions caused by Republican and Federalist politics and form the bedrock of the new nation. They looked to classical philosophers, reviving Aristotle and especially Cicero (who became one of the most popular classical authors during the 18th century). Greco-Roman antiquity celebrated friendship as a private bond that expanded to strengthen society as a whole. Freemasons believed friendly relations could strengthen the body politic, uniting American men outside their family orbit and into the realm of national civic life. They hoped sociability within their lodges would “cement together the whole brotherhood of men, and build them up an edifice of affection and love.”

THE LASTING IMPACT OF BROTHERHOOD

French brethren saw their lodges as utopias of friendship and civic virtue. On the eve of the French Revolution, Masons expressed deep anxiety about the moral corruption plaguing the kingdom. They believed friendship and morals could only be regenerated if the selfishness that corrupted human social relations was expunged. And, their surprising approach to rebuilding French society was to better one man at a time by identifying men whose virtue and upright morals stood out, then bringing them into the brotherhood. They believed that Freemasonry was the best possible environment for nurturing civil discourse and propagating friendships that benefited brethren and larger society; that virtue and friendship could impact the entire political system. As one lodge officer wrote: “We cultivate virtue. Offering the sovereign of the fatherland loyal subjects… adding to all the links that connect one man to another the most precious of all ties, that of a true and disinterested friendship. These are not futile tasks, but useful and precious ones, and it is Masonry that imposes them upon us.”

Freemasonry’s detractors during this time disavowed these rosy assessments. They saw Masonic friendship as dangerous to the nascent political order; as a rival set of allegiances echoing the powerful aristocratic networks of earlier days. A Committee of Public Safety representative closed all lodges in one French city during the Reign of Terror stating that Freemasonry: “prizes a far too intimate friendship over the austere rigidity that anchors the inflexibility of republicanism… Covered by the cloak of friendship, conspirators can take up arms against freedom.” In other words, while Masonry could form the bedrock of a new state, it could just as easily birth contrary political allegiances or trump patriotic sentiment. This statement is disparaging, but almost equally validating: Revolutionaries on both sides of the Atlantic recognized the immense power and possibility of Masonic brotherhood.

Since the Enlightenment, Freemasonry has continued to evolve into a worldwide fraternity, yet it remains anchored in the foundational values out of which it arose: philanthropy, friendship, and religious tolerance. Although these ideals are embraced throughout much of the world today, Freemasonry continues to play an important role in ensuring that these universal values remain at the core of our society. Just as we are not able to definitively chronicle Masonry’s role in the past, we cannot predict its capacity to shape the future. It is up to each Mason, and each lodge, to harness Freemasonry’s ability to effect lasting change.

Share this story with your lodge! All freemason.org articles may be repurposed by any Masonic publication with credit to the Grand Lodge of California. Print this article and post it at lodge; include it in your Trestleboard or website; email it to members; or use the buttons at the top of this page to share it on Facebook or Twitter.

“GIVE, GIVE, I PRAY YOU!

“GIVE, GIVE, I PRAY YOU!