Spring 2025 Issue Out Now: 175 Years

Author: jjapitana

Discovery Masonry on Freemason.org

Say hello to a series of brand-new web resources for prospects and new members available on freemason.org, the online home of the Masons of California. These new, interactive pages are designed to answer some basic questions about Freemasonry and how to join a lodge. Share them with prospects, new members, and anyone interested in learning more about the fraternity.

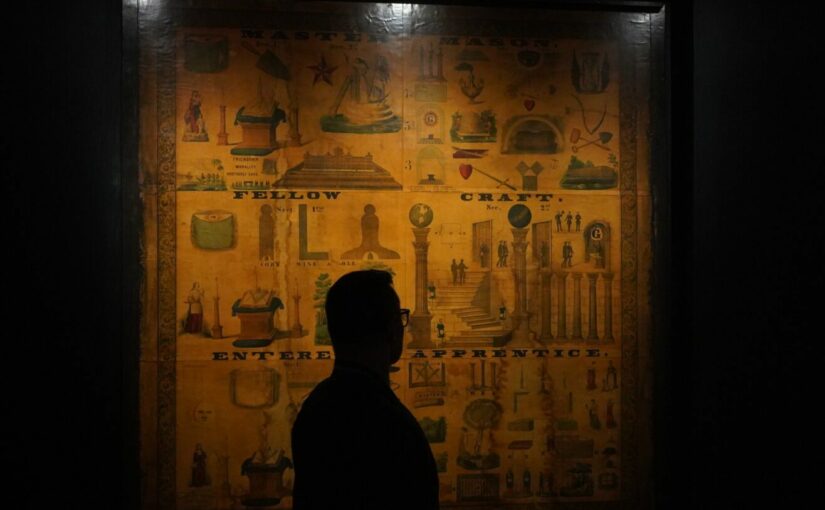

What is Freemasonry?

Becoming a Freemason

History of Freemasonry

Inside a Lodge Room

2024 Fraternity Report: The Win-Win

California Freemason: There’s No Place Like Lodge

Read more in the new issue at californiafreemason.org

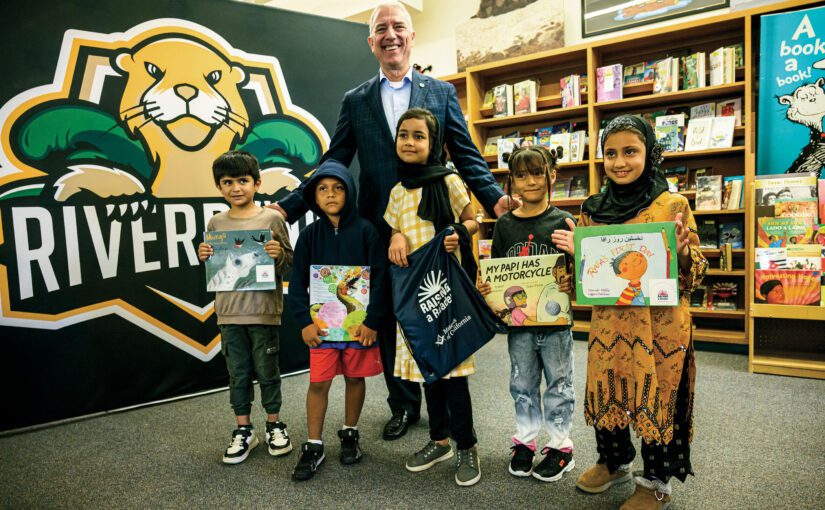

Could the simple act of joining a MasonicLodge be the key to rebuilding trust and strengthening democracy? Harvard sociologist Robert Putnam, author of Bowling Alone, thinks so. He argues that declining membership in social groups—like lodges, churches, and even bowling leagues—has contributed to rising polarization and social distrust.

Freemasonry offers a remedy: it fosters ‘social capital,’ creating connections that cross racial, political, and socioeconomic lines. By building trust and promoting civic engagement, Masons help strengthen the bonds that hold our communities—and democracy—together. Oh, and it might even help you live longer.

Winter 2024 Issue Out Now: A Sense of Belonging

Winter 2024 Issue Out Now: A Sense of Belonging

Why do people join the Masons? That’s one of the most common questions I’m asked by people who want to know more about this fraternity. We know that there are lots of reasons: Some had a father or grandfather who belonged to a lodge. Or a friend who introduced them to a member. Or just curiosity about the ritual and esoteric Masonic knowledge. Or a desire to improve as a husband, father, or partner.

people don’t necessarily talk much about, but what might be even more important, is the community aspect of our organization. When Masons gather in lodge, we’re coming together as a group of people with common values. We’re demonstrating servant leadership. We’re working with one another across political, ethnic, and socioeconomic lines.

people don’t necessarily talk much about, but what might be even more important, is the community aspect of our organization. When Masons gather in lodge, we’re coming together as a group of people with common values. We’re demonstrating servant leadership. We’re working with one another across political, ethnic, and socioeconomic lines.

Nowadays, that kind of cooperation is more important than ever. The harmony we see play out in our lodges is precisely the kind of thing we need in order to fight against the polarization and distrust that have become all too common . That makes our lodges important examples that our communities can follow—and it makes our members important leaders in the places they call home.

In this issue of California Freemason Magazine, we’re exploring the ways in which groups like the Masons can help members build social capital—a term first popularized by the sociologist Robert Putnam. With a new documentary film out now devoted to his work, it’s an ideal time to consider how Freemasonry can—and does—help build stronger and more resilient communities.

By fostering a true sense of community, inclusion, and belonging, Masonic lodges are lighting a path forward for the places we all call home.

![]()

Arthur L. Salazar, Jr.

Grand Master of Masons in California

A Conversation with ChatGPT About Freemasonry

The following is an exchange with OpenAI’s ChatGPT language-learning model chatbot. Read more about California Freemasonry at our website.

What’s the secret of Freemasonry?

Freemasonry is a fraternal organization that is often associated with secrecy due to its use of symbolic rituals and traditions. However, the organization states that its central principles are based on brotherhood, charity, and truth, and that its members take obligations to keep certain aspects of their ritual practices confidential.

The specific details of these rituals are not publicly disclosed and are considered private to members. It is widely believed that the “secrets” of Freemasonry refer to the ways in which these symbolic rituals are performed and the specific meanings they hold for members.

However, the exact nature of these secrets is not publicly known and is only shared among members.

What will make Freemasonry popular again?

It is difficult to predict what would make Freemasonry popular again, as popularity and cultural relevance can be influenced by many factors, such as changes in societal values, new forms of communication and organization, and shifting interests and beliefs.

However, some actions that Freemasonry organizations could consider to increase their visibility and appeal to a wider audience include: promoting their values and traditions through modern channels of communication, collaborating with other organizations and communities to serve the greater good, and being transparent about their practices and beliefs to dispel myths and misunderstandings.

Explain Freemasonry in the style of Kurt Vonnegut.

Freemasonry, my friend, is a strange and curious thing. Picture it like this: Imagine a secret society, full of handshakes and mysterious symbols, that values truth, charity, and brotherhood above all else. And they do it all while dressed in regal robes, surrounded by solemn music and elaborate ceremonies.

It’s a quirky blend of ancient tradition and modern morality, with its roots reaching back to medieval stonemasons, but now open to men from all walks of life. They gather in lodges, talking in cryptic phrases and performing strange rituals, all in the pursuit of personal improvement and a better world.

But let me tell you, there’s a good bit of humor and irony in it, too. These Masons take themselves quite seriously, but at the same time, they never forget to have a laugh and enjoy one another’s company. And despite all the secrecy and grandeur, at the heart of it all is a simple message of love and kindness.

Fall 2024 Issue Out Now: The Heroes of Freemasonry

Fall 2024 Issue Out Now: The Heroes of Masonry

What’s the best part of being grand master? I’m asked that often as I crisscross the state visiting as many lodges as I can. It’s certainly not the travel, which can be exhausting.

The simple answer is that the best part of this job is the people I’ve been blessed to meet on this journey. No matter where I go, I’m always impressed by the commitment of California Masons to one another, to their communities, and to our craft. I get to see brotherly love, relief, and truth put into practice in a million different ways—some big and dramatic, some small and close to home. But in every case, I know when I come to a Masonic lodge, I’m going to meet brothers who are taking the values and teachings of Freemasonry and putting them into action.

The simple answer is that the best part of this job is the people I’ve been blessed to meet on this journey. No matter where I go, I’m always impressed by the commitment of California Masons to one another, to their communities, and to our craft. I get to see brotherly love, relief, and truth put into practice in a million different ways—some big and dramatic, some small and close to home. But in every case, I know when I come to a Masonic lodge, I’m going to meet brothers who are taking the values and teachings of Freemasonry and putting them into action.

This issue is a celebration of those people, those lodges, and those ideas. It’s through their actions that we make Freemasonry come to life. It’s when we’re interacting with our neighbors, strengthening our community, or helping elderly members get the support they need that we most truly embody the Masonic spirit and push our craft forward.

G. Sean Metroka

Grand Master of Masons in California

A Conversation With Two Grand Masters

Summer 2024 Issue Out Now: Prince Hall, Then and Now

Summer 2024 Issue Out Now: Prince Hall, Then and Now

The summer issue of California Freemason Magazine is out now! And, for the first time ever, we’re devoting its pages to exploring the proud and vibrant history and the current state of Prince Hall Masonry. The issue was developed and executed in partnership with the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of California.

For nearly 170 years, our jurisdictions have progressed along separate and parallel tracks. But in recent years, the organizations have grown closer together, partnering on a range of philanthropic efforts and, at the local lodge level, joining together for everything from degree conferrals to social events.

In this issue, we are celebrating that partnership by taking a deep dive into the history and legacy of Prince Hall the man, as well as the history of the organization that today bears his name. We also examine ways in which neighboring lodges from our two grand lodges have found common ground; we explore the constellation of appendant and concordant bodies within Prince Hall Masonry, tell the history of a short-lived Filipino lodge boom within Prince Hall, and we profile several extraordinary members pushing the fraternity into the future. There’s also a can’t-miss interview between Grand Masters G. Sean Metroka and David San Juan, in which they discuss ways their groups can work together and what they see as the future of this historic partnership.

All in all, it’s a special issue of California Freemason Magazine and one we hope lives up to its name by highlighting and celebrating the wider world of Masonry in this state and remind everyone that regardless of race, ethnicity, or background, we are all California Freemasons.

Brick by Brick: Inside a Lodge-Building Boom

Read the new issue at californiafreemason.org

Since 2015, the Grand Lodge of California has made a priority of developing new Masonic lodges throughout the state. The idea is to both establish a greater presence in communities without an existing lodge, as well as to offer a greater range of choices to members.

It wasn’t always like this: Only five lodges that launched from 1970 to 2000 are still in existence. However, in the time since then, a whopping 36 new lodges have opened up (including two research lodges), along with four more under dispensation. Of those, 25 were established since 2017.

What has this lodge-building boom meant for the fraternity?

For Danny Foxx and the other charter members of Pilares del Rey Salomon № 886, it was a vision for a Spanish-speaking lodge that wouldn’t just meet and confer the degrees of Freemasonry, but also be a hub of Masonic education and philanthropy. At Seven Hills № 881 in San Francisco, Mark McNee says the challenge was to forge a new culture from scratch. Charlie Cailao, the current master of Palos Verdes № 883, points out that his lodge received its charter over Zoom. As a lodge without a home, his group relied on an unusual commitment from its members to stay together.

That was certainly the case for the eclectic band behind Ye Olde Cup and Ball № 880. Formed as the first “affinity” lodge in the state, Cup and Ball is made up of Mason-magicians who meet at Los Angeles’s venerable Magic Castle.

In this issue of California Freemason, we’re exploring what it takes to get these groups off the ground, how they define themselves within the landscape of Masonry in the state.

Ethnically diverse, culturally attuned, sometimes proudly eccentric, these groups show that while building a lodge is no easy feat, it’s also worth the reward.