Read the After Life issue: californiafreemason.org/cemetery

Masonic cemeteries offer a tantalizing glimpse into the history of the fraternity. Now, a pair of frontier graveyards are being brought back to life.

By Ian A. Stewart

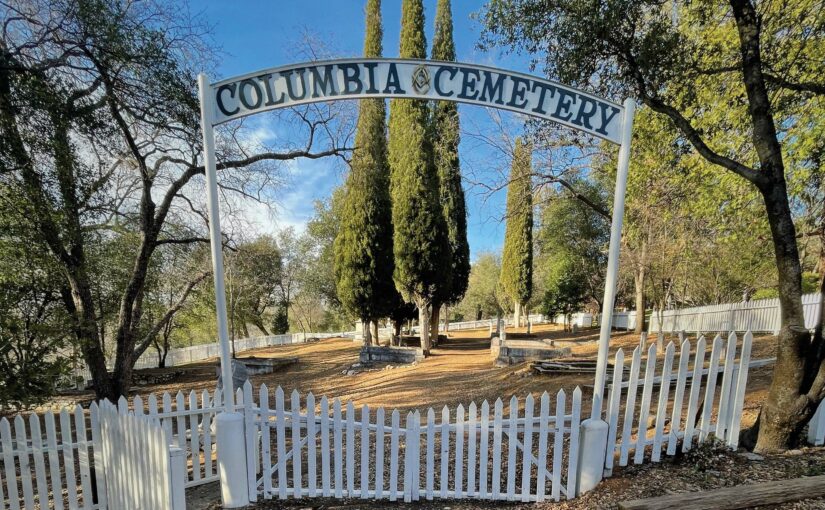

It was getting close to midnight when the dozen or so members of Logos № 861 walked out of the historic Columbia Masonic Hall and into the street. They’d gathered there for their annual lodge retreat, which features a degree conferral and what often turns into a lively festive board dinner. Now it was time for the unofficial third part of the event. Someone brought along a bottle, and the group headed toward the edge of the tiny gold-rush-era town in rural Tuolumne County, away from the din of the party.

The group hiked through the dark toward the tiny cemetery on School House Street where 110 early members of the fraternity had been lain to rest. In the quiet of the night, the group crossed the picket fence gate and gathered around a large granite stone where a memorial plaque was embedded. “Soft and safe to thee, my brother, be thy resting place,” it read.

The group wandered the overgrown park, stopping to look more closely at headstones dating back to 1853, the year the cemetery opened. At last the members gathered again and, with glasses held aloft, offered three salutes: to one another, to their fellow members around the world, and, finally, to those who’d entered the “celestial lodge above.”

Digging Deeper

Dylan Pulliam, a past master of the lodge, was among those present. For him, the impromptu service resonated deeply. “It’s spiritual,” Pulliam says. “It reminds us that our time on earth is short.” But it was more than that, too. Being among headstones as old as the state of California, the sense of history on display was practically palpable. “It makes you want to dig deeper,” he says.

Pulliam isn’t the only person to have that thought. Though seldom used these days and easily forgotten, cemeteries like Columbia’s play an important role in the history of California Masonry. In many places, they represent the close link between lodges and their communities.

Beginning in 1852, with the first records of California lodges establishing their own burial sites, Masonic cemeteries have provided a final resting place for some of the most important figures in the state’s history. From Shasta to San Diego, they’ve brought Masons together to celebrate, mourn, and pay homage. Packed to the brim with history, they really do make you want to start digging.

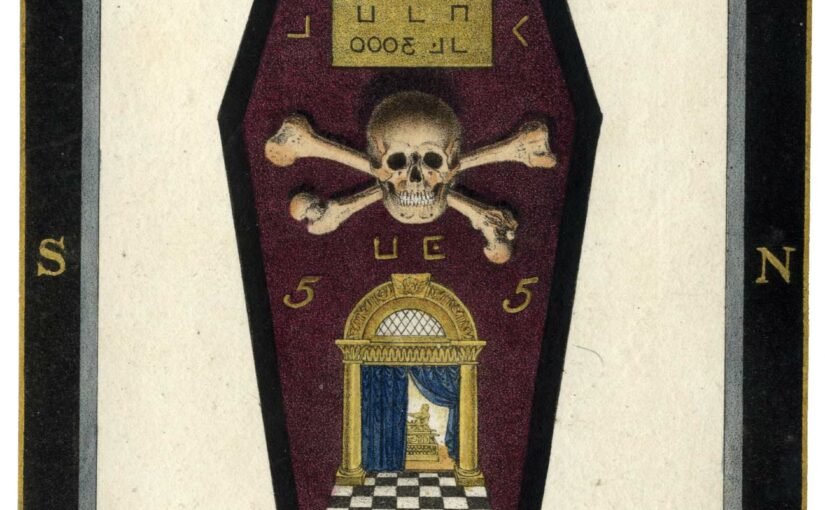

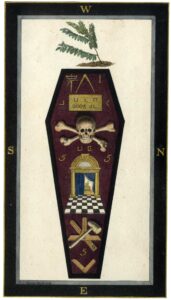

An Underground History

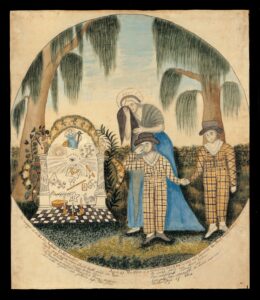

The first recorded Masonic funeral in the state occurred in 1849, when an unknown figure was found drowned in the San Francisco Bay. The man was carrying a silver shekel that indicated he was a Mark Master Mason, and had tattoos of various Masonic working tools and symbols. An account of the event published in The History of Nevada, 1881 recounts that “A large concourse attend[ed] the burial; the impressive service of the craft was read; the sprig of acacia was dropped into the grave by the hands of men from all quarters of the globe.”

During the Gold Rush, these sorts of Masonic send-offs were common. Back then, one of the most important roles of the fraternity was to provide a respectable burial for those who’d died penniless and far from home. Soon California lodges, many of them in the Sierra foothills, began to set aside or purchase plots for members and their families. To this day, Masonic cemeteries abound in the area along Highway 49, including sites in Jamestown, Sonora, and Calaveras County.

Among the most notable of these Gold Rush-era grounds was the Sacramento City Cemetery, where an annex was set aside for members of the city’s five Masonic lodges. By the late 19th century, they’d outgrown their corner and banded together to purchase an eight-acre plot adjoining the old graveyard, still known as the Masonic Lawn Association Cemetery.

By and large, these cemeteries were managed by the lodges that controlled them, and later by special associations made up of lodge members. That decentralization meant that it has long been unclear precisely how many Masonic cemeteries there are in California. And whether through sales of property, purchased plots, or co-management arrangements, questions inevitably arose over how lodges were meant to deal with their dead—questions that did not always have easy answers.

Keeping Up Appearances

By the middle of the 20th century, those issues were front and center. So Grand Master Louis Harold Anderson recommended the formation of a Masonic Cemetery Committee to review the status of all Masonic cemeteries in the state. “This is not only a safeguard to the resting places of the brethren who have gone this way before us, but it is a guarantee by California Masonry of today to future generations of Masons that they, too, may rest in peace until time is no more,” he wrote. In 1957, the committee made its first report: It concluded that there were 23 cemeteries owned by Masonic lodges in California; eight more owned jointly with another organization, often the Independent Order of Odd Fellows; plus 27 former Masonic cemeteries now being operated by an outside entity; and 23 instances in which a Masonic lodge owned plots within an existing cemetery.

Within a few years, the committee had taken charge of five historic graveyards whose parent lodges had either gone under or consolidated: These included cemeteries in Columbia, Jamestown, Fiddletown, and Michigan Bluff—all in gold country—and, for a time, Fallbrook Masonic Cemetery in San Diego County. It also took over management of the Peter Lassen Grave and Memorial near Susanville, in Lassen County. (Lassen is credited with bringing the first Masonic charter to California.) In each case, the upkeep of the cemeteries was supported with modest funds from the Grand Lodge and managed by volunteers.

For more than three decades, that committee ensured that the sites were maintained. But by the early 1990s, the transfer of responsibility had been passed through several other committees and boards. By and large, the matter had disappeared from public view. It wasn’t until 2013, when a new committee began looking into the tax implications of cemetery ownership that the issue came up again. After recommending slight changes to the California Masonic Code, the issue was largely put back to rest.

Portals to the Past

To visit a Masonic cemetery today is to be reminded of the fraternity’s long history in California—and its relationship to the earliest days of the state.

At the Shasta Masonic Cemetery, which was founded in 1864 and is operated by Western Star № 2, headstones include some of the most prominent figures in the town’s history. One of them is Daniel Bystle, a pioneer of early Shasta, a charter member of the lodge, and, ironically enough, the town’s first undertaker.

Another such local luminary is engineer Frank Doyle, the “father of the Golden Gate Bridge.” He is buried in the Masonic section of the Santa Rosa Rural Cemetery. In fall 2021, members of Santa Rosa Luther Burbank № 57 came together to install a memorial plaque there honoring Doyle and the more than 100 Masons buried on its grounds. “All the movers and shakers of early Santa Rosa are interred here,” says Paul Stathatos, a member of the lodge who volunteers at the cemetery. “There’s a lot of history here.”

A Personal Connection

In some cases, the local Masonic cemetery embodies larger historical trends. For many years, Ronald Andaya led a team of volunteers from Anacapa № 710 to clear weeds at the Oxnard Masonic Cemetery. Working there, he learned that the Masonic lodge that managed the cemetery had, in the early 20th century, donated a section of the plot to a nearby Buddhist temple so it could bury its Japanese Americans members there. Their remains were prohibited at the time from being interred in nearby Ventura. (The cemetery was recently sold to a private real estate developer, though the burial site itself will be preserved.)

For others, the connection to these places is personal. Dennis Huberty, a longtime member of Milton Lodge № 78 (since consolidated into Calaveras Keystone № 78), has for years served as the de facto head of the windswept Milton Masonic Cemetery, where headstones date to 1850. “It’s a typical pioneer cemetery,” he explains. “We’ve got the place fenced to keep the cattle from tramping all over it.” Huberty’s great-grandfather, William Samuel Dennis, was a past master of the Milton lodge and first worthy patron of its Eastern Star chapter. He was buried in the cemetery in the 1930s. Says Huberty, “You take care of your dead. It’s the most basic reason we’re in Masonry: To preserve history and honor those who were in the craft before us.

Resurrection

It’s with precisely that legacy in mind that a new effort is being launched to bring two historic Masonic cemeteries back to life.

The two cemeteries are the Columbia Masonic Cemetery, inside Columbia State Park in Tuolumne County, and a smaller site in nearby Jamestown. Both suffered from deterioration in recent years, but in November 2020, Grand Lodge staff took the first steps toward a full renovation of both sites. That meant repairing fencing and signage, clearing brush, and making other small repairs. At the same time, workers began making detailed surveys of the topography and conditions-assessment reports. The reports lay out a treatment plan for each monument, headstone, and mausoleum. “We had to determine, inventory, and account for every one,” says Khalil Sweidy, the Grand Lodge director of financial planning and real estate and a member of Columbia Historic Lodge. The effort involved using ground-penetrating radar and specially trained dogs to scour the grounds for unmarked remains.

The plans detailed in the two reports run to more than 30 pages each. They’re also, unsurprisingly, expensive. Now plans are being hatched to fund the most ambitious elements of the work needed to restore the two cemeteries to their former glory. “These cemeteries deserve some attention,” Sweidy says. “It reflects well on us when we take care of our cemeteries. We’ve done a lot of planning and prep work, but there’s still a lot to do.”

In the meantime, those buried in the old cemeteries aren’t going anywhere. And with their weathered monuments, they offer a poignant reminder of the links between generations of Masons. That point was driven home earlier this year for Sammy Hanes, a past master of Western Star № 2 who helps maintain the Shasta Cemetery. The graveyard had been practically wiped out during the 2018 Carr Fire, and a large acacia tree planted there was burned down. This year, though, the first green shoots began to reappear from its roots. Now, the Masonic symbol of regeneration is, once again, coming back to life.

For James Tucker, another member of Logos № 861, the Columbia cemetery isn’t just a trip back in time. It’s also a way to consider the future. “To be there,” he says, “you think about some lodge in the year 2100. For them to come to my grave and toast me, that’d just be the best thing ever.”

Today, these tend to be abstract ideas, jumping-off points for discussion of esoteric concepts. But historically,

Today, these tend to be abstract ideas, jumping-off points for discussion of esoteric concepts. But historically,  Any discussion of death and the afterlife inevitably leads to an ontological reckoning. To say that one believes in life after death or in the existence of the soul is an inherently spiritual statement, an expression of faith. Even distinguishing material and spirit, for some, raises uneasy metaphysical questions. It’s not surprising that for most Americans, death can be an uncomfortable topic.

Any discussion of death and the afterlife inevitably leads to an ontological reckoning. To say that one believes in life after death or in the existence of the soul is an inherently spiritual statement, an expression of faith. Even distinguishing material and spirit, for some, raises uneasy metaphysical questions. It’s not surprising that for most Americans, death can be an uncomfortable topic.